For those of you who are interested in philosophy and/or theology I would like to let you know that there is an awesome local philosophical-theology conference coming up in the L.A. area.

Here is the description:

Hope: Re-examinations of an Elusive Phenomenon

Hope is an elusive phenomenon. For some it is Pandora’s most mischievous evil, for others it is a divine gift and one of the highest human virtues. It is difficult to pin down but its traces seem to be present everywhere in human life and practice. Many are of two minds about whether this is a good thing or bad thing. Christianity as a comprehensive practice of hope cannot be imagined without it: Christians are not believers of dogmas but practitioners of hope. In other religious traditions the topic of hope is virtually absent or even critically rejected and opposed. Some see hope as the most humane expression of a deep-seated human refusal to put up with evil and suffering in this world, others object to it as an escapist reluctance and lack of courage to face up to the realities of the world as it is.

Hope is an elusive phenomenon. For some it is Pandora’s most mischievous evil, for others it is a divine gift and one of the highest human virtues. It is difficult to pin down but its traces seem to be present everywhere in human life and practice. Many are of two minds about whether this is a good thing or bad thing. Christianity as a comprehensive practice of hope cannot be imagined without it: Christians are not believers of dogmas but practitioners of hope. In other religious traditions the topic of hope is virtually absent or even critically rejected and opposed. Some see hope as the most humane expression of a deep-seated human refusal to put up with evil and suffering in this world, others object to it as an escapist reluctance and lack of courage to face up to the realities of the world as it is.

Half a century ago hope was at the center of attention in philosophy and theology. Ernst Bloch’s The Principle of Hope (1938-1947/1986), Jürgen Moltmann’s Theology of Hope (1964/1967), or Josef Pieper’s Faith–Hope–Love (1986/1997) are landmarks of the 20th century debate on hope. However, in recent years philosophers and theologians have been curiously silent on the subject of hope and the discussion has shifted to positive psychology and psychotherapy, utopian studies and cultural anthropology, politics and economy. This has opened up interesting new vistas. It is time to revisit the subject of hope, and to put hope back on the philosophical and theological agenda.

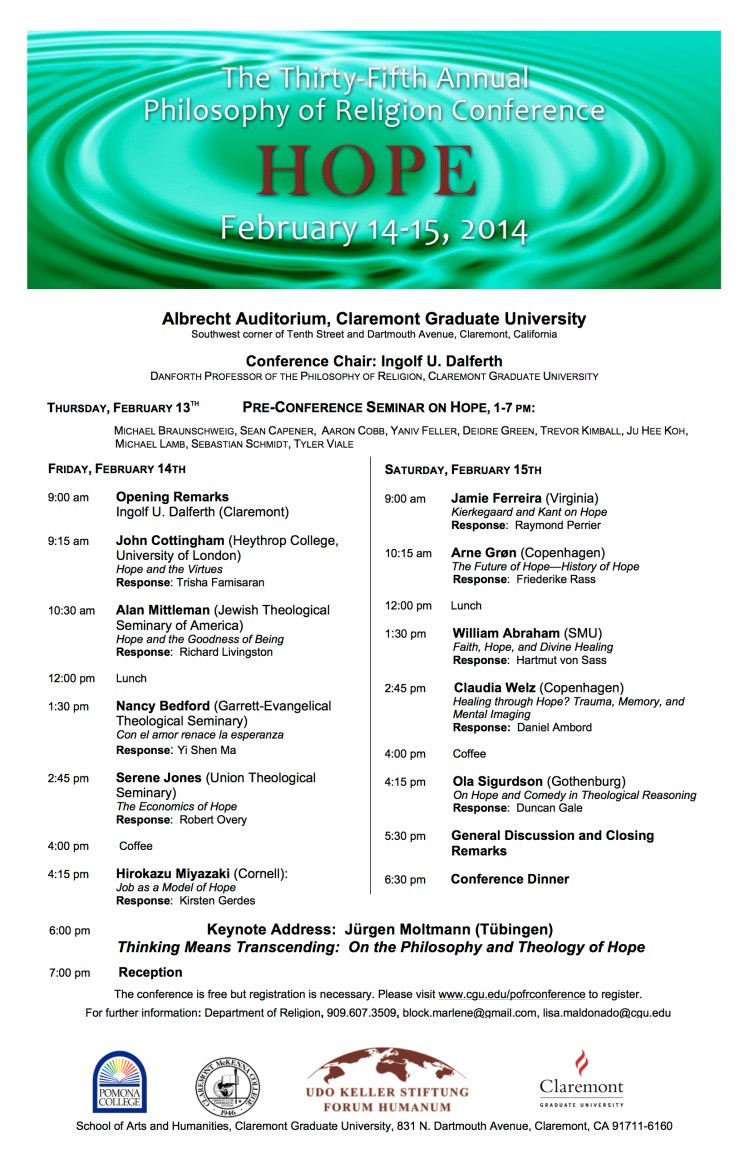

This is what this conference seeks to do, and there are many open questions. What is the phenomenon called hope? Is it the same topic that is studied in the various approaches to hope in psychology and politics, economy and theology? How does hope differ from belief and faith, trust and desire, expectation and confidence, optimism and utopianism? Is hope an emotional state or a feeling or a virtue? Does the absence of hope equal the presence of anxiety, fear or despair, or is there a human attitude or state that overcomes the opposition between hope and despair without being either of them? What is hope’s relation to promise and time, knowledge and action, self and community? Where are the limits of hope and what are its distortions? How is it to be distinguished form self-deception and error, wishful thinking and the irrational refusal to accept the world as it is? Does hope hinder religious believers from facing the tasks and challenges of the present life by orienting them towards a life to come? Is it a form of escapism to be shunned or a power of change to be appreciated? These and related questions we will explore at the 35th Philosophy of Religion Conference at Claremont, California, on February 14-15, 2014.

Speakers will include: Keynote speaker – Jürgen Moltmann (Tübingen), William Abraham (SMU), Nancy Bedford (Garrett-Evangelical Seminary), John Cottingham (Heythrop College, University of London), M. Jamie Ferreira (Virginia), Arne Grøn (Copenhagen), Serene Jones (Union Theological Seminary), Alan Mittleman (Jewish Theological Seminary of America), Hirokazu Miyazaki (Cornell), Ola Sigurdson (Gothenburg), Claudia Welz (Copenhagen)