See the message below from Allison Wiltshire

Hello!

—

Fuller Theological Seminary

Research Administrator AT project

Scattered Thoughts on Theology and Ministry…

See the message below from Allison Wiltshire

Hello!

—

He then praises the new films, Force Awakens & Rogue One, for how they bring back a sense of Reverence to the Force, and really to the world. Its really a great read. You should check it out. Thought it does contain some spoilers if you haven’t seen Rogue One Yet (who hasn’t!!!!).

Now, the real reason I’m writing this is to make a comment on his thesis. Barnes seems to think that the irreverence displayed in the sequels and the “commercialization” of the Force was more so a reflection of the film makers/writers pandering to audiences. The audiences wanted to see the Force in full effect! They wanted to see some spectacular fights and some super powers! However I disagree. I think the irreverent use of the force in the prequels is intentional. Reverence is something that only returns once the Jedi are forced into exile.

Think about the story line of the prequels. Part of it revolves around the idea that the Jedi losing touch with the Force. E.G. Yoda can’t even see the Sith before him and the council is a mess. They have lost touch with the Force and what it was intended to be used for. The fact that the Jedi irreverently start using the Force is part of the story line.

Also, I think there’s something to be said about the Jedi reclaiming the true “meaning” of the force when in exile. Exile tends to bring clarity. It’s in exile that one gets vision. Think of Scripture for a minute, who is known as The Seer? John, who is exiled on Patmos. When does Israel finally see its vocation? When does it begin to see its future liberation and God’s kingdom? It’s in exile. Think of the book of Ezekiel & Jeremiah… This is where the real parallels come out.

Ezekiel & Jeremiah chide the Elders of Israel for being BLIND, for making alliances with foreign kings. They chide the Elders of Israel for trusting in the Temple as a power, rather than God himself. Israel has sought safety in the power of God rather than in God himself. Much like the Jedi in the prequel, Israel has commercialized & mechanized God’s powers. In doing so, they have treated God irreverently, even desecrating the temple. Its only when Israel is sent off into exile that they begin to the real power of God. Similarly, its only in exile that the last surviving Jedi (Obi-Wan and Yoda) recover a greater reverence for the force.

At the end of each the year I put out the list of books I have read that year. Usually they consist of a lot of theology books, followed up by a good chunk of philosophy books, and a few fiction books thrown in. In 2013 I read 106 books. In 2014 I read 87 books. In 2015 I read 88 books. This year, my numbers went down drastically. However, that was mainly because I was in school again, reading lots of journals and book chapters, and writing a whole bunch. The numbers also dropped because I stopped reading at the gym. My workouts sort of changed (became more intense) so I no longer read while doing cardio. Anyway, this year’s total is 52 book. That’s one per week!

Books Read in 2016 = 52!

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

Lost Track of Dates

November

December

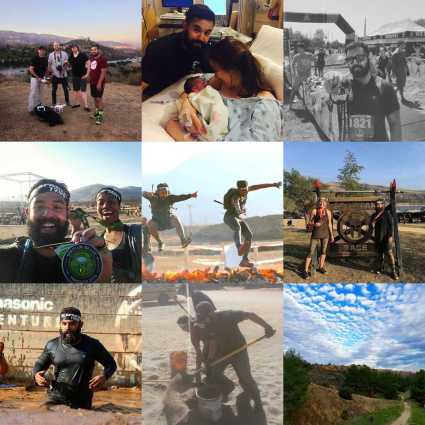

I’ve seen the meme’s all over the internet. 2016 was the year from hell! I get it… a lot of bad stuff happened (mainly Trump became President) and a lot of cool people passed away. In all honesty, for me 2016 was a pretty awesome year. First of all, my beautiful baby daughter, Shiloh Grace Woznicki, was born! My wife was a champ! Second, I started my PhD program at Fuller. That was such a blessing, and I really enjoy it. I get to study with and work alongside of some awesome people. Ministry was great too, I transitioned out of a leadership role and have successfully passed it on to someone else. And finally, I really started Spartan racing. I’ve been getting better and better. My goals for next year are to finish in the top 5% of at least one race. If you want to see some highlights from my 2017 check out my Top Nine from Instagram.

Having said all that, I know many of you are looking forward to the new year, it’s a chance, essentially to hit the reset button. I commend your optimism! And to you I would recommend you make one resolution:

BE YOURSELF! You know, “do you baby boo!” Be true to who you are and no one else. Follow your heart’s desires! Let your inner-self come out of that cacoon! Most of all, BE AUTHENTIC!

But before you dismiss me and think I’ve gone off the rails with some new agey, self-help, self-fulfillment pseudo-evangelical Christian style gobbledy gook. Here me out. Or better yet, hear out what Pastor Kevin DeYoung has to say…

If I had to summarize New Testament ethics in one sentence, here’s how I would put it: be who you are. That may sound strange, almost heretical, given our culture’s emphasis on being true to yourself. But like so many of the worst errors in the world, this one represents a truth powerfully perverted. When people say, “Relax, you were born that way.” Or “Quit trying to be something you’re not and just be the real you,” they are stumbling upon something very biblical. God does want you to be the real you. He does want you to be true to yourself. But the “you” he’s talking about is the “you” that you are by grace, not by nature. You may want to read through that last sentence again because the difference between living in sin and living in righteousness depends on getting that sentence right. God doesn’t say, “Relax, you were born this way.” But he does say “Good news, you were reborn another way.” (The Hole in our Holiness, 100)

He’s right….

In 2017 dare to be yourself. Dare to be the true you. The one who was reborn by God’s grace. Cuz if you are in Christ. That is the real you. That is who you are being made to be.

Paul’s New Perspective is Paul’s old perspective.

That’s the Garwood Anderson’s thesis in Paul’s New Perspective. In this long (+400 page) but very readable book Anderson argues against those advocates of The New Perspective on Paul and those of the Traditional Protestant Perspective (sometimes called the Lutheran view) showing that neither camp really gets Paul right. Paul cannot be understood simply from the NPP nor can he be understood simply from the TPP, rather what we see in Paul is development. Paul begins with the concerns brought up by NPP advocates and by the end of his career ends with concerns of the TPP.

Summary

Paul’s developing soteriology is supposedly seen in his development from concentration on “works of the law” to works more generally. Anderson argues that Romans, is a sort of transitional letter marking the shift between Paul’s old perspective and Paul’s new perspective. In Romans we see the transition between “the largely horizontal crisis of Gentile covenant membership independent of the law to a more vertically oriented reconciliation to God gained by faith apart from works, works of any kind.” (13)

Never disparaging either the NPP or the TPP, Anderson argues that both positions get a lot about Paul right, and that both sides have helped the church understand something important about its relation to God and the world. Some figures, like Wright, get it more right than others. For instance Wright in PFG rightly describes Paul’s logic as going vertical to horizontal, however the emphasis in Wright’s work is horizontal to vertical. Similarly, Dunn has helped reveal the horizontal problems Paul was dealing with when it came to the law’s role in acting as a dividing role between Jews and Gentiles.

In order to establish the case that Paul’s “new perspective” is actually his “old perspective” and that the traditional perspective is actually Paul’s “new perspective” Anderson has to establish this chronologically from his letters. Anderson notes that this is a bit problematic, as the position he argues for is not the majority view of critical scholarship (its not idiosyncratic either).

Having established the provenance of these letters Anderson turns his attention to two topics Works/Grace and Justification/Salvation in light of his reestablished order of letters. From this new order he shows that with regards to works, his early topic of “works of the law” shifts to “works” (full stop) with Romans acting as a transition between these two positions. Grace also follows this pattern. Beginning with Romans, grace is opposed to and excludes works. Concerning justification/salvation, in his later letters Paul recedes from the language of justification and prefers to use language of salvation and reconciliation. These two sections are made up of indepth exegetical and lexical work.

Assessment

So how convincing is Anderson’s argument that the New Perspective is Paul’s is actually Paul’s old perspective? I guess that comes down to one important factor, how convincing do you think Anderson’s assessment of Paul’s literary itinerary is? Do you find it plausible that Galatians is Paul’s first letter? If you think Galatians & Romans are fairly closely dated that his argument doesn’t really work. Do you buy a Roman (as opposed to Ephesian) provenance of the Prison letters? If you don’t then that throws a wrench in his entire reading of Pauline development as well. The problem with Anderson’s propsal is that you have to hold to a lot of minority positions regarding the composition of these letters. Neither the NPP or the TPP hangs upon one’s acceptance of a particular dating  of Paul’s letters, but Andersons’ thesis certainly does. This doesn’t necessarily mean that Anderson’s explanation is wrong. In fact, I would argue that it has a lot going for it! It breaks down some of the false dichotomies of the NPP/TPP debate, allows the church to incorporate the best of both perspectives, and has a lot of explanatory power. (His thesis even helps explain some of the concerns brought up by Apocalyptic readings of Paul!) But the fact that his whole argument is built upon the foundation of dates makes his foundation rather feeble. If one can decisively show his dating of Paul’s letters are wrong, his argument (in my opinion) falls apart.

of Paul’s letters, but Andersons’ thesis certainly does. This doesn’t necessarily mean that Anderson’s explanation is wrong. In fact, I would argue that it has a lot going for it! It breaks down some of the false dichotomies of the NPP/TPP debate, allows the church to incorporate the best of both perspectives, and has a lot of explanatory power. (His thesis even helps explain some of the concerns brought up by Apocalyptic readings of Paul!) But the fact that his whole argument is built upon the foundation of dates makes his foundation rather feeble. If one can decisively show his dating of Paul’s letters are wrong, his argument (in my opinion) falls apart.

All in all I would say that Paul’s New Perspective is a well written and well researched book, offering a via media in a rather creative way. Students of Pauline theology would do well to pick up this book, he does a fine job charging the various debates between NPP & TPP camps. His chapter on Post-NPP authors is fine as well. I can see myself assigning these chapters to students in a Pauline theology book, helping them get acquainted with contemporary debates in the Pauline literature. On top of all this, the summary of his position is rhetorically powerful, much like EP Sanders’ was: “covenantal nomism,” “getting in vs. staying in,” “solution to plight,” and “in short, this is what Paul finds wrong in Judaism: it is not Christianity.” Anderson’s position is quite memorable as well: “Paul’s New Perspective is Paul’s old perspective.” This catchy statement alone ensures the ideas in this book will be remembered, regardless of their staying power.

While I’m still not sure that Anderson’s proposal is convincing, it certainly is thought provoking. For that reason, I recommend you pick up this book. Its an position that deserves more thought and attention.

(Note: I received this book from IVP in exchange for an impartial review)

From a Review of Torrance’s Scottish Theology:

Dr. T.F. Torrance is among the immortals of Scottish theology, his work on the trinity an enduring priceless legacy. He has placed the homoousion at the heart of all our belief, reminding us that God has no face but Jesus. Even in his anger there is no un-Christlikeness at all. The electing (and the reprobating God) is non other than the incarnate Son. In Jesus’ sacrifice, God himself becomes the hilasmos. In his indwelling, God himself indwells us.

I and many others embraced these contributions with instant appreciation. But we saw in them no reason to repudiate our past. True, some of these emphases were not explicit in Scottish Calvinism. But they were implicit; or at least easily assimilated. We can welcome the new Trinitarian insights and weave them happily (if critically) into the legacy of Rutherford and Durham, Martin and Cunningham. Dr. Torrance does not need to discredit the past to create space for his vision.

-Donald McCleod EQ 72:1 (2000)

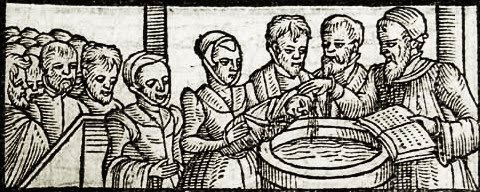

For the last +2000 years, the church has reflected on and celebrated the birth of our Lord and Savior. This is how it all started.

Merry Christmas!

A century after his death, William Poole excluded Calvin from his 1669 Synopsis Criticorum because supposedly Calvin was overly practical. Although in some ways Poole was off the mark with this critique, there is some truth in Calvin’s reputation as a pastor, primarily concerned with practical matters. Calvin’s practical and pastoral concerns emerge in his doctrine of baptism — specifically, as we will see, in and around two loci: the benefits of baptism for the Christian life and the benefit of baptism in the face of death.

Calvin begins his discussion of baptism by defining it as “the sign of initiation by which we are received into the society of the church, in order that, engrafted in Christ, we may be reckoned among God’s children.” The fact that his first line in the baptism chapter begins by speaking of the communal benefits of salvation seems to indicate that the “means of grace” aspect of this sacrament is secondary. However, he counters this possibility when he says that it is given to believers “first, to serve our faith before him,” and second, “to serve our confession before men.” (Calvin, 1304) Thus in explaining the reasons we are given baptism he places the “means of grace” aspect first. This is followed by discussion of three ways in which God’s grace is manifested to us through this particular sacrament.[1]

The first way baptism serves as a means of grace for believers is that it gives them proof that they are cleansed of their sins. Their sins are “abolished, remitted, and effaced that they can never come to his (God’s) sight, be recalled or charged against us.” (Calvin, 1304). As a sacrament, baptism does not actually cleanse believers of their sin; rather it gives certainty and knowledge of the fact that believers have been given this gift. In other words, baptism gives the believer assurance of the fact that they are cleansed of their sins. Anyone who serves in some pastoral capacity knows that a lack of assurance of salvation and forgiveness is a common issue among parishioners. One way people deal with this lack of assurance is by attempting to make penance for their sins. Calvin mentions this problem as well. In Calvin’s context, as opposed to our current protestant context, some attempted to get assurance through the “fictitious sacrament of penance.” Baptism provides assurance that penance cannot. Calvin says, “there is no doubt that all pious folk throughout life, whenever they are troubled by a consciousness of their fault, may venture to remind themselves of their baptism, that from it they may be confirmed in assurance of that sole and perpetual cleansing which we have in Christ’s blood.” (Calvin, 1307) Thus baptism serves as a means of assuaging guilty consciences which in turn may doubt the assurance of their forgiveness.

A second pastoral concern, not unique to Calvin by any means, is that Christians quite often fail to live in such a way that shows they are dead to sin and alive to righteousness. In other words, Christian tend to slip back into carnal ways of thinking and living rather than Spiritual ways of living. Christians can fall back into sexual immorality, impurity, lust, evil desires, greed, anger, range, malice, slander, and idolatry. In other words, they fail to put to death whatever belongs to their earthly nature.[2] How does Calvin address this pastoral problem? By arguing that baptism shows us the reality of our mortification in Christ, and our new life in him. (Calvin, 1307) In being baptized we are baptized in his death, but we are also “aroused to righteousness by example of his resurrection.” Thus baptism acts as a sign of the reality in which the Christian’s sinful nature has been put to death in Christ, and that they have been raised to life in righteousness. The reminder of mortification helps believers know that despite their sins, which give them so much trouble, they ought not cease to struggle, to have courage, and to spur on to full victory. (Calvin, 1312). It reminds struggling believers that the mortification of their sin will one day day be fully accomplished.

Thirdly, baptism acts as a token of our union with Christ. In virtue of being united to Christ, Christians have all the benefits which are necessary and sufficient for living out the Christian life. According to Calvin in baptism we are “so united to Christ himself that we become sharers in all his blessings.” (Calvin, 1307) Christians are told they are children of God, they are cleansed by his blood, they have a mediator, regeneration, resurrection, sanctification, and the righteousness of Christ.

Thus far we have seen the “means of grace” type benefits of baptism. These pastoral benefits Calvin addresses are in line with his belief that the sacraments are given for the arousing, nourishing, and confirming of our faith. Baptism, which is received “from the hand of the Author himself” is given to Christians as a gift which will help them life which is pleasing to God.

In addition to stressing that baptism arouses, nourishes, and confirms God’s grace to believers, there is another pastoral element in Calvin’s baptismal theology. This appears in how he addresses what he takes to be wrong teachings about infant baptism. In this regard, Karen Spierling[3] does much to shed light upon what caused the rise of these teachings.

Spierling explains that baptism in Roman Catholic theology baptism was the rite by which an infant “was freed from evil spirits, purified of original sin, and sanctified in God’s promise of salvation through Christ.” (Spierling, 65) Given the high infant morality rate and theology which said that if a child had not been purified of original sin through baptism they would not receive salvation, one can imagine parent’s concern for ensuring that their child be baptized no matter what. Naturally, parents were worried about the fate of the soul of their child. For their child to miss baptism understandably brought much anxiety. For this reason, emergency baptisms were often performed by midwives when they believed the child would not survive before being baptized in the church. There were even instances of “resuscitation” that occurred in order that children who died before baptism could be baptized and thus “saved.” (Spierling, 79-80).

Given the fact that Roman Catholic theology about infant baptism was deeply ingrained into the minds of Christians who became reformed, its not surprising to hear that emergency baptisms continued in reformed and Lutheran cities. Spierling notes that in some areas, like Scotland, leaders allowed for the gradual adoption of “more thoroughgoing protestant doctrine” by allowing the “solace of emergency baptism” without “explicitly granting its theological underpinning.” (Spierling, 78) Calvin, however, was not so accommodating. He vehemently opposed the Roman Catholic understanding of infant baptism. Many of the reasons why he did so were pastoral. First, emergency infant baptism (not to mention resuscitating baptism) represented a reversion into the error of separating word from sacrament. In Calvin’s opinion, separating word from sacrament led to superstitious practices. Calvin wanted to avoid superstitious practices because people tended to put their trust in those practices rather than in Christ. Second, Calvin wanted to counteract the anxiety that Roman Catholic theology of baptism potentially brought to parents. In fact, Calvin believed that the reformed doctrine had greater potential to give parents confidence that their dead infant was saved. Spierling argues that “Calvin was not, however, so callous as to want to leave parents thinking that an infant who died unbaptized would be stuck in limbo or refused salvation. Instead he argued that baptism was important as a sacrament, yet not vital to salvation.” (70) Calvin declares that God adopts the babies of believers before they are born, thus parents of believers could be saved if the parents themselves were saved. This was supposed to assuage the anxiety suffered by parents whose children died unbaptized. Whether or not it actually provided comforting assurance to parents is questionable, nevertheless it was supposed to fulfill this pastoral function.

Confirming the fact that Calvin was truly a practical theologian we have seen that Calvin’s theology of baptism was intended fulfill the pastoral functions of encouraging believers, both in their Christian life and in the face of the death of their children. Whether Calvin’s theology accomplished this end in Geneva is questionable. Nevertheless, we can say at the heart of his baptismal theology was the notion that God has given the church this sacrament for the sake of its benefit.

[1] Concerning sacraments in general Calvin says, “They do not bestow any grace of themselves, but announce and tell us, and (as they are guarantees and tokens) ratify among us, those thing given us by divine bounty.” (Calvin, 1293)

[2] See Colossians 3:5-11.

[3] See Infant Baptism in Reformation Geneva, WJK 2005.

Vulnerable. Not the first word that comes to mind when you think about strong leaders. Yet, this word, “Vulnerable,” is what Mandy Smith, lead pastor of University Christian Church in Cincinnati, Ohio, suggests should characterize strong Christian leaders.

In The Vulnerable Pastor: How Human Limitations Empower Our Ministry Smith attempts to debunk current leadership wisdom as not only being harmful, but impossible. The image of somebody who is always strong, always has their stuff together, is never wrong, never wavers, and is extremely self-confident is the exact opposite of what Smith suggest Christian leaders should be like. Instead a Christian leader should be marked by vulnerability. Specifically, this vulnerability should recognize and understand our human constraints. Recognizing these constraints makes our ministry more sustainable “and guards us against disillusionment and burnout.”

of somebody who is always strong, always has their stuff together, is never wrong, never wavers, and is extremely self-confident is the exact opposite of what Smith suggest Christian leaders should be like. Instead a Christian leader should be marked by vulnerability. Specifically, this vulnerability should recognize and understand our human constraints. Recognizing these constraints makes our ministry more sustainable “and guards us against disillusionment and burnout.”

As the former director of a college ministry in a large church in the LA area I knew I could benefit from reading Smith’s book. I sort of live in the “mega-church” world, which is mostly characterized by the leadership images Smith decries. I constantly struggled, despite pressing on in ministry, with the notion that I didn’t fit the “pastor-mold.” I still struggle with it! Even though its never expressed, it is implicitly there. I’m just not one of those pastors. I’m shy, introverted, intellectual, liturgical. Again, not your typical mega-church type leader. Throughout the book Smith shares her struggles with not fitting the mold. Told mostly in story form, she expresses how difficult it was to be herself as leader, when the world (i.e. CHURCH WORLD) told her that wasn’t enough. It was only when she was bold enough to admit that she didn’t have what the world asked of her, and she didn’t need to have it, that she began to find joy in her ministry.

Here are some helpful quotes from her book:

When we’re at our desks preparing our sermons and something snags our hearts, can we set aside our work long enough to be worked upon? Can we trust that the teaching of our congregations is not primarily our work but God’s work, which he wants to being with us? (92)

What if we began with our human limitations and shaped a ministry from that? Like a child pouring pennies on a candy store counter, asking, “How much candy can I get with that?” we can look at the time, gifts, energy, and ideas we have and ask, “How much church can we get with that?” (105)

If it’s right for me to be here (and I beliee it its) and it’s alright for me to be limited (and I believe it its), I have to trust that there’s a way to do this job without it destroying me. If he gave the church to humans, he must have a way for humans to do church. (105)

One way I equip my leaders is to remind them it’s their job to equip others. We’re not soloists; we’re choirmasters. Its not our job to do the work but to give the direction: to pick the note, choose when to start and wait for the community to shape the fullness of the song. (108)

All in all, I found this book quite helpful. There were so many positive messages in it that I needed to hear once again. Being a pastor, or any kind of Christian leader, is not about being enough…. Its about being willing to revel in our own weakness and in God’s strength.

Note: I received this book from IVP in exchange for an impartial review.

A varied cast of characters has taken interest in Julie Canlis’s Calvin’s Ladder: A Spiritual Theology of Ascent and Ascension. This book has caught the attention, in the form of reviews, of church historians, philosophers, and pastors. Those writing from the perspective of these vocations have all noticed strengths and weaknesses in Canlis’s book which are unique to their perspective. In this brief “review of reviews” I would like to highlight some of the features which make up these reviews and provide some comments on the merits of these assessments.

The first set of reviews consists of reviews by church historians. I began by  examining a booknote by Tony Lane, professor of Historical Theology at the London School, in a 2012 edition of Evangelical Quarterly (EQ 84.3, 280-1). He begins by noting that this book was birthed out of Canlis’ doctoral studies at St. Andrew’s and that it received the 2007 Templeton Award for Theological Promise. He lavishes praise upon the book when he says “it is easy to understand why” it won this award. His review of this book is relatively short. He notes that ascent of the soul is a concept generally greeted with suspicion in the Reformed tradition, but that Calvin has essentially “reformed” it from its Platonic and Neo-Platonic tendencies. He also mentions her comparison between Calvin’s doctrine and Irenaeus’s doctrine. He commends her for restraint in not citing direct influence, but wonders whether tracing out Irenaeus’s influence on Calvin would be an interesting topic for future study. In terms of critique, Lane rightly notes that “there is occasionally a tendency in her exposition of participation to swallow up other categories of Calvin’s thought.” This is a critique which appears in several other reviews as well. However, one might wonder, “If participation is the central theological theme of Calvin wouldn’t it make sense for all other categories to fall under this one category?” In order for this sort of defense to stick, however, one would have to prove that participation is Calvin’s central theme. The other review I examined was written by Sujin Pak, who is now the Assistant Research Professor of the History of Christianity at Duke Divinity school. Her review of Calvin’s Ladder can be found in Modern Theology (MT 27.4, 717-20). She begins by noting the trend in Calvin studies to focus on Calvin’s doctrine of union with Christ and participation in Christ and says that Canlis now adds an important and eloquent contribution to this topic. Like Lane she notes how Canlis persuasively shows that Calvin reforms the traditional theologies of Ascent. Despite being persuaded regarding ascent, Pak displays some hesitancy regarding Canlis’s understanding of Calvin’s theology of participation. She notes that it might not be as important as Canlis has made it out to be. She cites the fact that Calvin does not clearly make the connection between participation and election as evidence that it may not be as central as Canlis makes it out to be. She also wonders whether Canlis overlooks the forensic nature of participation in Calvin. As a minor point of critique Pak points out that Canlis doesn’t address commentaries on key passages that evoke participator themes, for example Romans 8. Despite these shortcomings she sees Calvin’s Ladder as a generally persuasive and eloquent rereading of Calvin’s understanding of salvation and sanctification. Of these two critiques by church historians one would expect significant attention to be paid to the historical claims Canlis makes, however both of these reviews are lacking in this area. Lane’s review completely lacks this feature, though he might be excused given the length of his review. Pak’s critique from a historical perspective is limited to her suggestion that Canlis should have read other texts. Neither critique is historically significant. One would expect more from church historians.

examining a booknote by Tony Lane, professor of Historical Theology at the London School, in a 2012 edition of Evangelical Quarterly (EQ 84.3, 280-1). He begins by noting that this book was birthed out of Canlis’ doctoral studies at St. Andrew’s and that it received the 2007 Templeton Award for Theological Promise. He lavishes praise upon the book when he says “it is easy to understand why” it won this award. His review of this book is relatively short. He notes that ascent of the soul is a concept generally greeted with suspicion in the Reformed tradition, but that Calvin has essentially “reformed” it from its Platonic and Neo-Platonic tendencies. He also mentions her comparison between Calvin’s doctrine and Irenaeus’s doctrine. He commends her for restraint in not citing direct influence, but wonders whether tracing out Irenaeus’s influence on Calvin would be an interesting topic for future study. In terms of critique, Lane rightly notes that “there is occasionally a tendency in her exposition of participation to swallow up other categories of Calvin’s thought.” This is a critique which appears in several other reviews as well. However, one might wonder, “If participation is the central theological theme of Calvin wouldn’t it make sense for all other categories to fall under this one category?” In order for this sort of defense to stick, however, one would have to prove that participation is Calvin’s central theme. The other review I examined was written by Sujin Pak, who is now the Assistant Research Professor of the History of Christianity at Duke Divinity school. Her review of Calvin’s Ladder can be found in Modern Theology (MT 27.4, 717-20). She begins by noting the trend in Calvin studies to focus on Calvin’s doctrine of union with Christ and participation in Christ and says that Canlis now adds an important and eloquent contribution to this topic. Like Lane she notes how Canlis persuasively shows that Calvin reforms the traditional theologies of Ascent. Despite being persuaded regarding ascent, Pak displays some hesitancy regarding Canlis’s understanding of Calvin’s theology of participation. She notes that it might not be as important as Canlis has made it out to be. She cites the fact that Calvin does not clearly make the connection between participation and election as evidence that it may not be as central as Canlis makes it out to be. She also wonders whether Canlis overlooks the forensic nature of participation in Calvin. As a minor point of critique Pak points out that Canlis doesn’t address commentaries on key passages that evoke participator themes, for example Romans 8. Despite these shortcomings she sees Calvin’s Ladder as a generally persuasive and eloquent rereading of Calvin’s understanding of salvation and sanctification. Of these two critiques by church historians one would expect significant attention to be paid to the historical claims Canlis makes, however both of these reviews are lacking in this area. Lane’s review completely lacks this feature, though he might be excused given the length of his review. Pak’s critique from a historical perspective is limited to her suggestion that Canlis should have read other texts. Neither critique is historically significant. One would expect more from church historians.

The second type of review I examined was written by a professor who holds a position at Baylor as assistant professor of Religion and Philosophy. Charles Raith, whose review of Calvin’s Ladder appears in the International Journal of Systematic Theology (IJST 15.2, 233-5), has written various works on Calvin and participation, thus he seems to be an appropriate person to review this book. Like many others Raith notes the similarities to Billings’ work on participation. Raith focuses on Canlis’ account of Calvin’s relational ontology. For Canlis, the soul’s ascent is rooted firmly in a relational ontology, which is rather different from traditional accounts which are rooted in a substantialist ontology. Raith notes that she also makes a case for a relational ontology in the works of Irenaeus.

Although Raith appreciates Canlis’s work in showing that God desires to draw humanity to himself, Raith questions Canlis’ understanding of Calvin’s teaching on participation. He believes that Canlis has squeezed Calvin into the contemporary ideas within social Trinitarianism of “personhood” and “relational ontology.” He says that one gets the feeling Canlis has “left the sixteenth century building and entered into contemporary debates about person.” In doing so, Canlis has promoted “a major ontological shift in the name of Calvin.” He concludes his review by saying, “Canlis’s imposition of current trends in relational ontology and personhood onto Calvin’s thought, and the claims that result, raise some concerns.” This seems to be an understatement given the rest of his critique of Canlis’ book. It should be said that Raith’s critique has some merit, Canlis certainly uses relational language which may not be as prominent in Calvin’s own work, however Canlis is certainly not squeezing Calvin into social Trinitarian ideas of personhood and relational ontology. The reasons I say this is that Canlis’ account of participation in Christ and union with the divine life of the Trinity is heavily influenced by the theology of T.F Torrance (though she is not very explicit about this.) Torrance is by no means a social Trinitarian. Torrance also never proposes that the ontological category personhood is grounded in relationship (as Zizioulas and other social Trinitarians do). Read in light of Torrancian theology one can make sense of her statements regarding the Trinity and ontology without accusing her of falling into contemporary categories put forth by social Trinitarians.

The third type of review I examined was a review written by pastor Jamin Coggin in the Journal of Spiritual Formation & Soul Care (4.2, 316-8). Jamin currently serves as the pastor of spiritual formation and retreats at Saddleback Church. He begins by noting Canlis’ vision for the book which is “concerned with a story line that has always been at the heart of Christian mystical theology and spiritual praxis: the ascent of the soul.” He believes that Canlis has done a fine job of articulating a clear theology of participation in the Triune life of God from a distinctly Reformed perspective. She does a fine job of showing how Calvin avoided the ever prevalent Hellenistic schemas of ascent and has placed Christ at the center of the believer’s ascent into the life of God. Taking the perspective of a pastor, Coggin notes that her book offers fodder for reshaping spiritual formation in a more theologically robust way. He commends the book for avoiding the tendency of books on spiritual formation to be overly practice oriented and not sufficiently grounded in theology. He critiques the book for not engaging with Bonaventure’s theology of ascent and not devoting sufficient attention to the topics of prayer and spirituality. Throughout his critique of Calvin’s Ladder, one can see his pastoral colors emerge. Coggin is concerned about spiritual formation and Christian practices. He reads Canlis’ book in light of how helpful it will be for the work of pastors. He concludes that it will in fact be a very helpful resource for accomplishing the pastoral task.

Having briefly looked at three types of reviews, those written by historians, a philosophical theologian, and a pastor, several common themes emerge. The first is that Canlis has done a service to the church by adequately showing that Calvin’s spirituality can be understood as being rooted in participation in Christ. Historians, theologians, and pastors commend her for showing that a theology of ascent is actually a part of the Reformed Tradition. A common critique of her work is that she failed to address the reviewer’s field of expertise, i.e. she should have engaged x or y work. This is not a substantial criticism. However more substantial than this criticism is the critique that Canlis has molded Calvin in her own image, i.e. a 21st century theologian working in a highly relational/social Trinitarian context. The way Lane articulates this critique is quite tempered, whereas Raith’s articulation of this critique is more forceful. However, I have shown that Raith’s critique may be a bit too strong.

When reviewing a book like Canlis’s, which toes the line between history/theology/praxis, it is helpful to have a multitude of voices and disciplines weigh in. Hopefully this review of reviews has helped to highlight the multifaceted contributions that Calvin’s Ladder can make to various fields of study.